Patent searches are an important source of information on the state of the art, both in a scientific context and even more so in an economic context.

In the field of chemistry and life sciences, special requirements are placed on a patent search in order to evaluate the texts found well and present the results in a meaningful way. This topic was addressed by graduate chemist Dr. Andreas Fuß, whom the participants were able to look over the shoulders of in a GO-Bio initial online seminar on 26/06/2025 and learn from him as an experienced researcher how best to proceed with the search and what to consider.

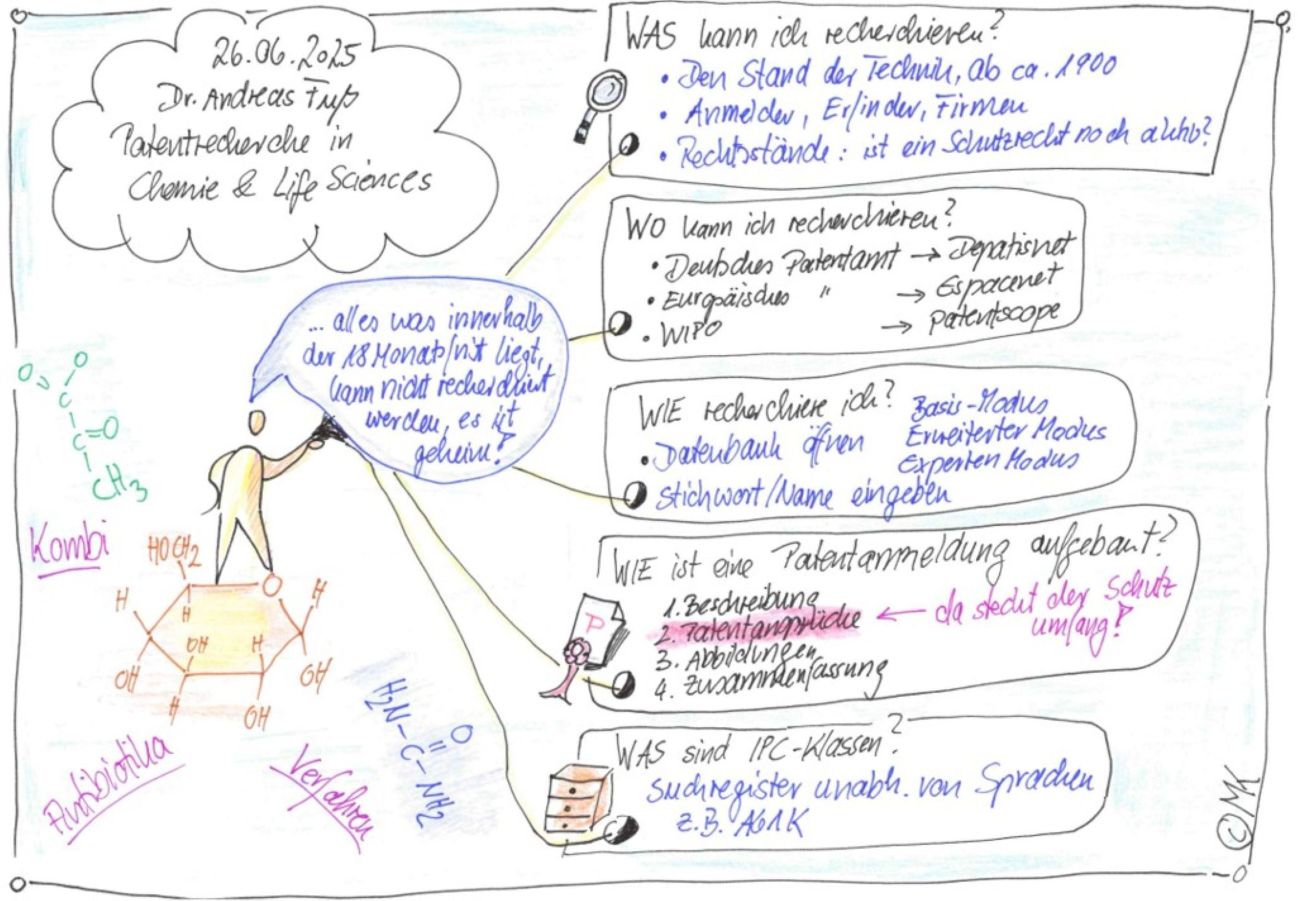

First, Dr. Fuß presented the aspects that can generally be searched for. The usual thing, he said, is that you want to find out more about the state of the art for a keyword or a combination of keywords. So what does the patent world know about a certain antibiotic or a receptor or an active ingredient against a certain disease? In some cases, there is information going back into the past to around 1900. You can also search for applicant names, e.g. to find out which intellectual property rights a particular company has filed. You can also search for inventor names to find out whether a particular person has already invented something. Dr. Fuß emphasized that there is a period of 18 months in the past during which documents are not disclosed but are secret. So we only find out what was published 18 months ago at the earliest, he revealed. Research into the Freedom to Operate (FtO) is also very important. Here, we look in particular at the legal status of the documents found, which shows whether a property right is still active or has already lapsed. For a patent application, it is important to be new and inventive in relation to the prior art, but for product development it is particularly important not to infringe active property rights, or rather to circumvent them.

After this rather theoretical introduction, the participants were motivated to search the patent databases themselves using their own keywords and concerns. The databases of various patent offices and the search masks were presented. Using depatisnet from the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DPMA) as an example, the participants continued with a simple basic search. Dr. Fuß then explained that there is also an advanced mode and even an expert mode, which offers the searcher more options, e.g. to work with Boolean operators and truncations, or also allows negative exclusions, because if you are looking for glasses as a visual aid, you don't want to search for toilet seats.

In order to better understand the documents found, some of which are very extensive, Dr. Fuß outlined the usual structure of a patent specification and made it clear that the entire text and also the figures represent knowledge of the prior art, but that the patent claims are particularly relevant when considering the scope of protection.

He also gave a very clear explanation of the drawer register of the IPC classes, which all patent offices worldwide use uniformly so that certain technologies can be searched for regardless of the term and language. However, according to Dr. Fuß, this is more for professionals or if you are looking for clear technologies such as dentistry, which can be found in IPC class A61C.

Participants were able to ask questions at any time and compare their results with those of Dr. Fuß. At the end, Dr. Fuß showed how to use the translation function of the Patent Office to be able to read and evaluate texts found in foreign languages.

Ms. Ascensi bid farewell to the participants, thanked them for coming and referred to the next GO-Bio initial events and also to other seminar days that are still being planned.